Sean Diment, OMS-III

Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine

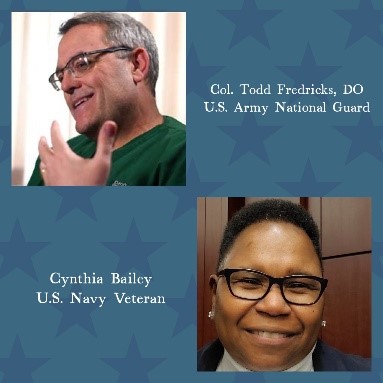

Each year on November 11, America observes Veterans Day. While many celebrate with parades or moments of reflection, it’s equally important for medical professionals to recognize the lasting health impacts of military service. U.S. Army Colonel Dr. Todd Fredricks, DO, State Surgeon for the West Virginia Army National Guard, and U.S. Navy veteran Cynthia Bailey, share their personal experiences and offer expert insights into enhancing primary care for veterans.

Two Lifetimes of Service

Colonel Fredricks has 33 years of military service, including multiple combat deployments and participation in humanitarian, peacekeeping, and emergency missions. His expertise is in operational medicine, with degrees from the U.S. Army War College and U.S. Air Force Air War College, including a Master of Strategic Studies from the former. Dr. Fredricks also works as an Associate Professor of Family Medicine at Ohio University’s Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine.

Bailey, who first joined the Army Reserve in 1987, switched branches and became active duty in the U.S. Navy shortly after, then serving as a culinary specialist until 1997. She chose to leave the Navy to help take care of her daughter who required surgery for a ventricular septal defect. During her military service, she sustained injuries from a severe car accident where she and her husband had to be cut out of their vehicle after being struck by an 18-wheeler. Further, years of standing on steel decks, and other injuries to her knees and lower limbs, created chronic pain issues.

After encouragement from neighbors and support from veteran service organizations like AMVETS and the Disabled American Veterans (DAV), she successfully secured disability benefits through the VA. This experience inspired her to advocate for others. "I wanted to help because someone helped me," Bailey said, reflecting on her work with the DAV.

Bailey served as the commander for Virginia’s DAV Chapter 20, First Junior Vice of the state chapter, and is now the chaplain for the 6th National DAV District. She has helped countless veterans access benefits and be connected to a community, especially through her famous cookouts, where she shows off her culinary expertise from the Navy.

Unique Health Challenges for Veterans

Fredricks shared that veterans often face health challenges stemming from both their military and civilian lives. These include PTSD, chronic pain, traumatic brain injuries (TBIs), increased risk for suicide, and service-related physical conditions.

"Military service exposes individuals to unique occupational risks,” Fredericks shared. He noted exposures like repeated concussive blasts, foreign diseases, and moral trauma. To maximize support for these issues in primary care, Fredricks stressed the importance of a detailed military occupational history for all veteran patients. "Veterans should be asked about their years of service, exposures, and any health issues they believe are connected to their service," he advised.

Bailey echoed the need for continuity of care, sharing her frustration with the VA’s bureaucracy and a lack of continuity. "Since I’ve been in the VA system, I haven’t had the same primary care provider for two consecutive years. This inconsistency, paired with long waits for specialty care, can be retraumatizing for veterans, who must repeatedly recount their experiences to new providers.” Bailey also acknowledges the burnout experienced by physicians, accounting for the high turnover, and emphasizes that she appreciates their willingness to serve veterans as well.

In addressing the high rate of veteran suicides, Fredricks implores all providers: “If you are worried about suicide, if it even crosses your mind, act on it. Know your local VA resources, and don’t be afraid to ask the vet if they are contemplating suicide. Just ask. They might be very forthcoming. If they are contemplating suicide, follow through and work to get them help, even if you have to start with non-VA resources.”

Building Trust and Rapport

Both Fredricks and Bailey emphasized the critical role of trust in the provider-patient relationship. Fredricks encourages healthcare providers to approach veterans with curiosity and an open mind. "Assume nothing. Listen receptively. Believe the veteran when they share their experiences."

Fredricks also shared his experience with a VA psychologist who made an assumption about his service. “I once had a VA psychologist question my PTSD because he assumed all military physicians worked in a field hospital. Aside from the fact that a field hospital in combat can be a psychologically agonizing place, my psychologist was given an education when I explained that I spent my last tour of Iraq supporting Naval Special Warfare units with casualty evacuation backup.”

Fredricks continued, “I can’t emphasize too much the importance of being curious and not judgmental. Ask a lot of open-ended questions and interview as if you care. You might think you know what a truck driver does in the military, but you might be very wrong. At one point in the Iraq War, the most dangerous occupation in the Army was that of 88M (Motor Transport Operator). You are going to get one chance, and if you arrogantly assume that an 88Mike shouldn’t have PTSD or a TBI because ‘all they did was drive a truck,’ your session might end abruptly, with very colorful language.”

Bailey also emphasized the critical importance of building trust through open communication. She recalled a breakthrough moment when her physician asked, “Is there anything else?” At first, she hesitated. There was something else, but she denied. The physician paused, sensing the hesitation, and then asked again. That time, it opened the door to a deeper conversation about her mental health struggles, and she spent the afternoon being connected to counseling and other veteran support groups.

Important Connections for the Primary Care Physician

Fredricks suggests that primary care physicians familiarize themselves with VA systems, collaborate with veteran service organizations, and understand key health initiatives like the PACT Act and Agent Orange registry. Two essential roles to be aware of for a primary care provider, he explained, are the VA Hospital Patient Care Advocate and a County Veterans’ Service Officer. The VA Hospital Patient Care Advocate helps ensure issues arising from patient care are quickly handled, also facilitating crucial record releases. This can help providers determine what care a veteran receives through the VA and what they receive outside of the VA, but he encourages providers to always ask the veteran as well. The County Veterans’ Service Officer can help veterans access their benefits, as it can be a complicated process. Bailey, however, received help through outside veteran advocacy groups who also perform this crucial job.

Bailey recommends that providers spend time with veterans outside of the clinic to truly understand their unique needs, for instance, by attending community events or talking to local veteran chapters. “How you treat a veteran is different than a civilian,” she said. “There are multifactorial underlying factors tied to military service.”

The Call to Serve

Both Fredricks and Bailey highlight the pride and resilience of veterans. Fredricks expresses gratitude for those who care for veterans, urging providers to always remember, "Veterans bring stories of resilience and sacrifice. The best thing you can do is listen and care."

Fredricks, who is entering his last year of military service, also offered another idea to help providers build their understanding of military service: joining the reserves or National Guard. “There is nothing like doing to create knowledge,” he said.

In her closing thoughts, Bailey reflected, "We [veterans] are broken in different ways, but we still love our country. But, if given the opportunity to serve again, we would."

Resources for Primary Care Providers

Col. Fredricks’ “Veterans’ Project” documentary

Col. Fredricks’ “3 Questions” short video