This paper was submitted as part of Dr. Perrine's application for ACOFP Fellowship, which recognizes exceptional national, state, and local service through teaching, authorship, research, or professional leadership. Visit the ACOFP Fellows page to learn more about fellowship and the nomination process.

ABSTRACT

Lyme disease, the most common vector-borne disease in the United States, is caused by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi, transmitted to humans through the bite of the infected Ixodes scapularis tick.1 Typical symptoms include fever, headache, fatigue, and the characteristic erythema migrans skin rash. When left untreated, Lyme disease can spread to the nervous system, cardiovascular system, and musculoskeletal system.2 Antibody testing is valuable when performed with validated methods at an appropriate interval after tick bite. Most cases of Lyme disease can be treated successfully with a brief course of oral antibiotic therapy. Infection may be prevented with certain insect repellents and by prompt removal of attached ticks. This article will briefly examine a case of pediatric facial nerve palsy and review the clinical presentation, diagnosis, and evidence-based treatment of Lyme disease. This topic is particularly relevant to the osteopathic family physician, who is likely to encounter patients with Lyme disease exposure and infection in the outpatient, urgent, and emergent care settings.

CASE REPORT

LM is a 4-year-old white male brought to the walk-in urgent care center by his mother after an unintentional strike on the forehead by a water bottle while playing with friends two days prior. He complained of minor headache immediately following this incident, but symptoms resolved after one administration of pediatric acetaminophen. On the day of presentation, he developed acute right-sided facial drooping in the absence of fever, headache, dizziness, visual disturbance, neck pain, and rash. No relevant past medical or surgical history. His physical examination revealed right facial nerve paresis with mild speech slurring (Figure 1). No other findings were identified on his cardiopulmonary, neuromuscular, or skin exams. He was prescribed prednisolone 2 mg/kg/day totaling ten days to treat presumptive Bell’s palsy, then discharged to home after Lyme disease testing was obtained. Two days later, his Lyme disease antibody screen resulted positive with a positive confirmatory IgM immunoassay. He was then prescribed doxycycline 4.4 mg/kg/day totaling 21 days. His pediatrician documented complete resolution of his right-sided facial drooping during a follow-up encounter two weeks after initiation of antibiotic therapy.

Figure 1. Bell’s Palsy in Children.3

OVERVIEW

Lyme disease, first identified in Old Lyme, Connecticut in 1975, is the most common vector- borne disease in the United States.4 A recent estimate using commercial insurance claims data suggests that Lyme disease was diagnosed and treated in ~476,000 patients in the United States annually during 2010-2018.5 According to data reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) during 2008-2015, the age distribution of patients with probable and confirmed Lyme disease is bimodal, with peaks among those aged 5-9 years and 50-55 years. Most reported cases are among white males. Fourteen states, all located in the Northeast, mid- Atlantic, and upper Midwest regions, account for >95% of all reported cases.6

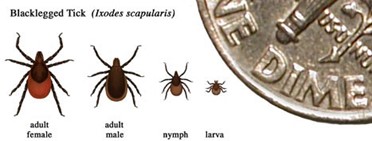

Lyme disease is most commonly caused by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi, which is transmitted to humans through the bite of infected blacklegged ticks (or deer ticks, Ixodes scapularis). In their larval and nymphal stages, these ticks acquire Borrelia when feeding on infected small mammals, such as the white-footed mouse. They utilize deer as their preferred hosts, however deer are not infected with Borrelia and do not infect ticks.1 Nymphal ticks pose a particularly high risk to humans due to their vast abundance, small size (Figure 2), and salivary protein immunosuppressive effects, which prevent hosts from feeling pruritis or pain from their bite.7 In most cases, Lyme disease infection requires tick attachment for 36 to 48 hours to allow Borrelia adequate time to migrate from the tick midgut to its salivary glands.

Figure 2. Relative Sizes of Blacklegged Ticks at Different Life Stages.8

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

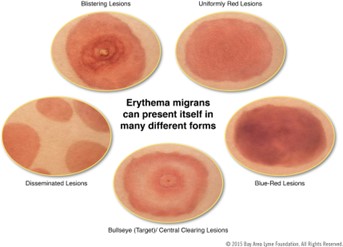

Early localized symptoms of Lyme disease occur three to thirty days after a tick bite. These include fever, chills, headache, fatigue, myalgias, arthralgias, lymphadenopathy, and erythema migrans (EM).9 The appearance of the EM rash can vary widely (Figure 3). It occurs in 70-80% of cases, presenting at the site of the tick bite after a seven-day latent period, on average. It expands gradually over several days and sometimes clears as it enlarges, resulting in the characteristic “bullseye” or target appearance. The EM rash may radiate warmth, but should be neither pruritic nor painful. It typically fades in three to four weeks.

Figure 3. The Many Different Forms of Erythema Migrans.10

Early disseminated symptoms of Lyme disease occur days to weeks after the initial rash appears. These include severe headache, nuchal rigidity, facial droop, severe large joint pain and swelling (particularly in the knee), palpitations, dizziness, numbness and tingling, and possibly multiple EM lesions.2 Late disseminated symptoms of Lyme disease include encephalomyelitis, polyarthritis, and persistent atrioventricular block, also known as Lyme carditis.

DIAGNOSIS

Lyme disease may be diagnosed clinically if a patient presents with the EM rash and a history of tick exposure in an endemic region. No additional testing is necessary for these patients. The CDC and Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) recommend serology in patients with suggestive symptoms that do not include the EM rash.11 The initial diagnostic test should be a sensitive enzyme immunoassay, followed by a secondary enzyme immunoassay or western immunoblot for specimens yielding positive or equivocal results.12 Antibodies against Lyme disease develop over a period of several weeks, therefore testing is unlikely to consistently result positive until 4-6 weeks after infection.13 IgM and IgG produced in response to Borrelia burgdorferi may persist for years following antibiotic therapy. Even if persistently elevated, these levels are not indicative of ineffective treatment or chronic infection. Repeated serologic testing is not recommended in current guidelines. The IDSA supports the submission of removed ticks for species identification, but advises against testing removed Ixodes ticks for Borrelia burgdorferi, as the presence or absence of Borrelia does not reliably predict the likelihood of clinical infection.14

TREATMENT

The IDSA, American Academy of Neurology (AAN), and American College of Rheumatology (ACR) published clinical practice guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of Lyme disease in November 2020. They recommend that prophylactic antibiotic therapy be given only to adults and children within 72 hours of removal of an identified high-risk tick bite, but not bites that are equivocal or low risk.14 If a tick bite cannot be classified with a high level of certainty as a high-risk tick bite, then a watch-and-wait approach is recommended.14 A tick bite is considered to be high-risk only if the tick is identified as Ixodes scapularis, the bite occurred in a highly endemic area, and the tick was attached for >36 hours. If those three criteria are met, then a single dose of doxycycline (200 mg for adults, 4.4 mg/kg for children) may be considered.14

For adult and pediatric patients with erythema migrans or Lyme disease complicated by neurologic, cardiac, or rheumatologic manifestations, the IDSA recommends oral antibiotic therapy with doxycycline.14 Alternative antibiotic choices include amoxicillin, cefuroxime, and azithromycin.14 Traditionally, doxycycline has been avoided in children <8 years of age due to concerns about staining permanent teeth, however recent data indicate that dental complications are not associated with doxycycline, in contrast to older tetracyclines. For this reason, current treatment guidelines recommend the use of doxycycline regardless of age.15 The suggested duration of antibiotic therapy varies according to the complexity of infection, delineated in Tables 1 and 2 below:

| Table 1. Adult Treatment | First Line | Alternative |

| Erythema Migrans | Doxycycline 100 mg BID x10-14 days | Amoxicillin 500 mg TID x14 days |

| Neurologic Disease | Doxycycline 100 mg BID x14-21 days | N/A |

| Lyme Carditis | Doxycycline 100 mg BID x14-21 days | Amoxicillin 500 mg TID x14-21 days |

| Lyme Arthritis | Doxycycline 100 mg BID x28 days | Amoxicillin 500 mg TID x28 days |

| Table 2. Pediatric Treatment | First Line | Alternative |

| Erythema Migrans | Doxycycline 4.4 mg/kg/day divided BID x10-14 days (max 100 mg/dose) | Amoxicillin 50 mg/kg/day divided TID x14 days (max 500 mg/dose) |

| Neurologic Disease | Doxycycline 4.4 mg/kg/day divided BID x14-21 days (max 100 mg/dose) | N/A |

| Lyme Carditis | Doxycycline 4.4 mg/kg/day divided BID x14-21 days (max 100 mg/dose) | Amoxicillin 50 mg/kg/day divided TID x14-21 days (max 500 mg/dose) |

| Lyme Arthritis | Doxycycline 4.4 mg/kg/day divided BID x28 days (max 100 mg/dose) | Amoxicillin 50 mg/kg/day divided TID x28 days (max 500 mg/dose) |

Treatment for severe Lyme disease with neurologic or cardiac manifestations and Lyme arthritis refractory to an initial course of oral antibiotic therapy is not discussed in this clinical review. Those patients may require parenteral therapy, hospitalization, and/or specialist consultation.

Although most cases of Lyme disease resolve with a brief course of antibiotic therapy, patients sometimes experience persistent or recurring nonspecific symptoms, such as fatigue, pain, and cognitive impairment, which last for more than six months after treatment. This condition is known as Post-Treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome (PTLDS).16 There is no indication for prolonged antibiotic therapy for these patients, as studies have failed to demonstrate superior long-term outcomes when compared to patients who have received a placebo. The risks of prolonged antibiotic exposure outweigh any potential benefits in patients without objective evidence of reinfection or treatment failure, such as arthritis, meningitis, or neuropathy.14

PREVENTION

Ticks are most commonly found in grassy, bushy, and wooded areas, or on animals. They are most active during the warmer months – April to September. Treating clothing and gear with permethrin 0.5% and treating exposed skin with N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide (DEET), picaridin, or oil of lemon eucalyptus (OLE) may repel ticks.17 If a tick becomes attached to the skin, then it should be promptly removed using fine-tipped tweezers by grasping the tick as close to the skin’s surface as possible, and then pulling upward with steady, even pressure.

As of 2023, no human vaccines for Lyme disease are available. The only human vaccine to advance to market was LYMErix, which was available from 1998 to 2002. In clinical trials, that vaccine was found to confer protective immunity in 76% of adults after three doses.18 It was ultimately withdrawn from the market due to slow clinical adoption, high cost, public fear of adverse effects, and negative media coverage. There are multiple vaccines available for the prevention of Lyme disease in dogs.

KEY POINTS FOR THE OSTEOPATHIC FAMILY PHYSICIAN

- Fewer than 20% of patients recall a tick bite preceding the erythema migrans rash

- There is no evidence to support commercial tick testing for Borrelia infection.

- Lyme disease testing may not yield a reliable result until 4-6 weeks after tick bite.

- Prophylactic antibiotic therapy should only be offered to patients in a highly endemic area within 72 hours of removal of an Ixodes tick that has been attached for ≥36 hours.

- Doxycycline is the drug-of-choice for treatment of adults and children with erythema migrans or Lyme disease with neurologic, cardiac, and rheumatologic manifestations.

- Patients who have persistent or recurring nonspecific Lyme disease symptoms, such as fatigue, pain, or cognitive impairment, do not benefit from additional antibiotic therapy.

REFERENCES

- Lyme Disease Transmission. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, August 15). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/transmission/index.html.

- Signs and Symptoms of Untreated Lyme Disease. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, August 15). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/signs_symptoms/index.html.

- Bell’s Palsy in Children. Royal College of Emergency Medicine. (2023, August 15). Retrieved from https://www.rcemlearning.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/Bells-Palsy-image-1.jpg.

- Steere AC, Malawista SE, Snydman DR, Shope RE, Andiman WA, Ross MR, Steele FM. Lyme arthritis: an epidemic of oligoarticular arthritis in children and adults in three connecticut communities. Arthritis Rheum. 1977 Jan-Feb;20(1):7-17. doi: 10.1002/art.1780200102. PMID: 836338.

- Kugeler KJ, Schwartz AM, Delorey MJ, Mead PS, Hinckley AF. Estimating the Frequency of Lyme Disease Diagnoses, United States, 2010-2018. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021 Feb;27(2):616-619. doi: 10.3201/eid2702.202731. PMID: 33496229; PMCID: PMC7853543.

- Schwartz AM, Hinckley AF, Mead PS, Hook SA, Kugeler KJ. Surveillance for Lyme Disease — United States, 2008–2015. MMWR Surveill Summ 2017;66(No. SS-22):1–12. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6622a1.

- Hovius, J. W. R. (2009). Tick-host-pathogen interactions in Lyme borreliosis. [Thesis, fully internal, Universiteit van Amsterdam]. (2023, August 15). Retrieved from https://pure.uva.nl/ws/files/816561/62941_thesis.pdf.

- Relative Sizes of Blacklegged Ticks at Different Life Stages. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, August 15). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/images/tick_sizes.jpg?_=05071.

- Pace EJ, O'Reilly M. Tickborne Diseases: Diagnosis and Management. Am Fam Physician. 2020 May 1;101(9):530-540. PMID: 32352736.

- Skin Rashes. Bay Area Lyme Foundation. (2023, August 15). Retrieved from https://www.bayarealyme.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Rash-Illustration.png.

- Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, et al. The clinical assessment, treatment and prevention of lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America [published correction appears in Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(7):941]. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(9):1089-1134.

- Mead P, Petersen J, Hinckley A. Updated CDC Recommendation for Serologic Diagnosis of Lyme Disease. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:703. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6832a4

- Lyme Disease Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, August 15). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/faq/index.html.

- Paul M Lantos and others, Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), American Academy of Neurology (AAN), and American College of Rheumatology (ACR): 2020 Guidelines for the Prevention, Diagnosis and Treatment of Lyme Disease, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 72, Issue 1, 1 January 2021, Pages e1–e48, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1215.

- H. Cody Meissner, Allen C. Steere; Management of Pediatric Lyme Disease: Updates From 2020 Lyme Guidelines. Pediatrics March 2022; 149 (3): e2021054980. 10.1542/peds.2021-054980

- Post-Treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, August 15). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/postlds/index.html.

- Preventing Tick Bites on People. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, August 15). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/prev/on_people.html.

- Poland GA, Jacobson RM. The prevention of Lyme disease with vaccine. Vaccine. 2001 Mar 21;19(17-19):2303-8. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00520-x. PMID: 11257352.